Look Around You

In a second, I’m going to ask you to lift your head up and look around your current location.

I want you to take a quick tally of everything you can see that has a textile component. That is, any fabric, anything woven.

Okay, take thirty seconds and have a look.

…

Even if you’re in the most barren, plastic-fantastic food mall, there is still a staggering amount of fabric in use. To start, everything anyone is wearing is most likely woven or knitted (unless they’re wearing vinyl, but don’t share that).

Lampshades, cushions, the rug on the floor at your feet, the covering on the chair you’re sitting on, the coat you wore to get here, your hand bag, possibly your wallet, the little zip pouches in your handbag. The seats in your car, the mats on the floor.

Your umbrella, your hat, your gloves.

The curtains, the sheets you sleep on, the pillow cover and the pillow case. The coverings on top of the sheets, and the mattress cover itself. The towels in the bathroom, and the washcloth. The mats on the floor of the bathroom.

Handkerchiefs. Scarves. Shawls.

Hardbound book covers.

Speaker covers.

The rags used to wipe up spills, varnish wood, clean up handy-man projects.

Flags. Pennants. Tents. Sleeping bags. Backpacks.

Spacesuits.

I could go on, but you get the general idea. Fabric is everywhere.

In this modern age, the way we use fabric has changed considerably. We often use paper for napkins, for example. Plastic sometimes replaces canvas (tents, for example, and movie screens). We no longer use cloth to wrap and store food, because plastic containers do a better job (although there are arguments for returning to fabric once more). And everyone knows that fabric grocery bags are the better choice.

How Fabric Is Made Now

Modern textiles are all made in factories, except for tiny home-based artisan businesses that hand-make fabrics—usually only for pleasure.

Modern textiles are all made in factories, except for tiny home-based artisan businesses that hand-make fabrics—usually only for pleasure.

The factories might be huge, fully-automated things, or third world sweat shops where humans supply most of the labor and skill.

It is fascinating to see modern fabric being manufactured. Check out this five minute video of denim being made, from the arrival of raw cotton to the shipping of bolts of finished denim. Notice the lack of people checking the fully-automated processes.

Depending on how old or small the plant equipment is, more human intervention is required, although even the smallest and oldest factories can create hundreds of yards of fabric in a day.

Before industrialization, a single loom could weave about six yards a day…and that was a very long, uninterrupted day!

How Fabric Used To Be Made

That six yards a day was a standard used in the early 19th century, with flat “modern” looms, and it was only the weaving part of the process.

No matter what the fiber is that makes the fabric—wool, flax, silk, cotton or (these days) man-made fibers—they all go through a similar basic process that hasn’t changed since man stopped wearing animal skins

No matter what the fiber is that makes the fabric—wool, flax, silk, cotton or (these days) man-made fibers—they all go through a similar basic process that hasn’t changed since man stopped wearing animal skins

Collecting/making/harvesting

Cotton and flax is harvested, wool is shorn from sheep, cashmere and goat’s hair from goats, silk is harvested from silkworm cocoons, etc.

The shearing of sheep/goats was usually done by the man of the family, but from there, the rest of the process was given to the woman.

The harvesting of silk, flax, even nettles, and other plant fibers used for weaving in pre-industrial times usually fell to the woman.

Cotton is a very new fabric in historical terms, only becoming popular in the 19th century, which was the start of industrialization and mechanical picking processes, although in some areas of the world, humans picked the bolls (the southern United States, for example).

Processing for spinning

Cleaning, carding, combing, breaking down the plant fibers to remove the husks, softening, and aligning the fibers for easier spinning.

Cleaning, carding, combing, breaking down the plant fibers to remove the husks, softening, and aligning the fibers for easier spinning.

There are usually multiple stages in this step, to take the fibers from raw to ready-to-spin.

Dying

Dying sometimes happens when the fibers are in the raw findings stage, sometimes after spinning and sometimes after weaving. Cashmere, for example, and tweed, are usually dyed in the findings stage.

Pre-industrialization, the dyes were all made from natural sources.

Purple, for example, came from a rare mollusk found along the coast of Italy. It was so hard to find and so time-consuming to make that only the highest of nobles–emperors and their families—were allowed to wear purple. Hence the expression “the wearing of the purple” to denote high born ranks.

Spinning

This is the process that turns the raw fibers into the twisted strands used for weaving. The tighter the twist, the finer the material. Strength and evenness of spinning will affect the final woven cloth. Looser spinning and more fibers taken up with each twist will produce a thick, coarse strand.

This is the process that turns the raw fibers into the twisted strands used for weaving. The tighter the twist, the finer the material. Strength and evenness of spinning will affect the final woven cloth. Looser spinning and more fibers taken up with each twist will produce a thick, coarse strand.

Spinning wheels are a relatively modern invention. Before wheels were invented, women spun by hand, using a distaff to hold the raw fibers, and a spindle that had weight and could be spun with the finger and thumb to twist the fibers. The spun strand was wound onto the spindle. Here’s a short video of a woman hand-spinning.

The distaff used in spinning gave rise to the expression “on the distaff side of the family” – meaning, the female side of the family, as spinning was exclusively a woman’s work. The male side was less commonly called the “spear side” [and I’m biting my tongue as I write that].

Once a strand was spun, it might be twisted with another to create a thicker thread, called a ply thread. This was (and still is) most often used for knitting.

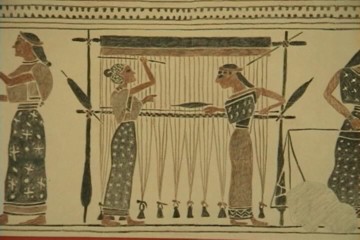

Weaving

Weaving was first done on handlooms, then bigger and more complicated looms were developed throughout history. The process is still highly manual. Threading a loom is nearly always (still) a manual process and very time consuming.

Weaving was first done on handlooms, then bigger and more complicated looms were developed throughout history. The process is still highly manual. Threading a loom is nearly always (still) a manual process and very time consuming.

The finishing processes can vary wildly. Once fabric comes off the loom, it can be used as is. It may need cleaning, dying, stiffening, or a brushed finish, sealing, waterproofing/waxing. Two layers of fabric can be glued together to create a laminated, sturdy, heavy-duty fabric.

Once the finished treatments are done, the fabric is ready to be used. Usually, that involves:

Sewing

Cutting and sewing fabric into the finished item is the final step to a finished garment or product. These days, sewing of garments is all factory based, although a strong home-sewing industry has resurged in the last few years, now that patterns and techniques can be shared on-line and products and tools acquired from far away. Also, many sewists prefer to make their own clothes and accessories to avoid sweat shop labor-made items.

Prior to industrialization, everything was hand-sewn.

Why am I telling you about cloth-making?

As this post has gone on for far too long already, I’ll finish it up in a future post. The answer may (or may despressingly not) surprise you.

Cheers,

.

Get the news that no one else does. Sign up for my newsletter.

For a short while, you get a bundle of ebooks, free, when you sign up, as a Starter Library. Details here.

Wow found this really interesting, now I maybe understand why “purple” is my favourite colour…lol…xx

Explained a lot. Thank you…xx

There’s more to come! This was a long post by the time I was done – had to break it up into two parts.

t.

Wow, you really like to write about everything. But it’s always interesting and I always learn something new.

Thank you!

It’s my curiousity bump. I research for books and trip over interesting factoids and wow-gosh stuff, so I write about it here.

Anyone reading my historicals will spot where the research creeps in. Then you can stab the page and go “aha!”

t.